![]()

I've always had a soft spot for

Hare-um Scare-um (1939), Bugs Bunny’s third cartoon. As a kid, I actually ranked it among the best Warner Bros. shorts: I liked the gags, I liked the goony formative version of Bugs, I even memorized the song he sang. While I grew out of considering the film a classic, I remained interested by new discoveries related to it.

Michael Barrier learned, for example, that

Hare-um marked the first time the new star was advertised as Bugs Bunny (even though he wasn’t named in the film itself). More recently, Mike Van Eaton and Jerry Beck found original art to a

promo brochure that was part of that ad push.

When I first heard talk of

Hare-um—a cartoon I thought I knew inside and out—perhaps having an extra scene or scenes, I didn't believe it. I went into

denial. But soon, an urban Internet legend had developed to the point where I finally became curious. Could I get to the bottom of it? What would Duck Twacy do? What would...

Snopes do?

Legend: Hare-um Scare-um (1939), the third cartoon to feature a prototypical Bugs Bunny, has been edited for violence in the print we usually see (above). The full, original version ended with Bugs and his "whole family" beating the stuffings out of hunter John Sourpuss and his dog, perhaps so violently that only their decapitated heads are left to roll away over the hill for the closer.

Status: PARTIALLY TRUE.Examples:[Jerry Beck and Will Friedwald, The Warner Brothers Cartoons, 1981]

"The censored ending has the hunter being beaten up by the rabbit and his whole family."

[Visitor to The Unofficial Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Page, c. 1998]

"This is what I was told was missing at the end: All of the rabbits attack the hunter (not Elmer Fudd, but a one-shot hunter) and his dog. The smoke clears and we see two heads—the hunter's and the dog's—rolling off down the same roadway into the sunset as the iris brings the toon to a close."

[Visitor to Toon Zone, 2002]

"Supposedly the rabbits beat up the hunter and dog, causing a cloud of smoke. When the cloud clears you see the heads of the hunter and dog rolling down the road."

[Visitor to Misce-Looney-Ous blog, 2008]

"I don't know about 'heads rolling into the sunset,' but in the version I've seen, the rabbits just start beating the heck out of the hunter and his dog, then iris out. If there's a longer version (and there could be), I haven't seen it."

[Visitor to YouTube, 2009]

"yea i think i have seen both on cartoon network in 2000 when i wuz 4 im 13 now iand i think i remember seein both in my long term memory i remember the dog and hunter gettin beat up and their heads are rolling down a hill." [SIC!]

Origins: The 1998 version of the rumor, posted to the Censored Cartoons Page and recovered through the

Wayback Machine, turned out to be the earliest mention I could find anywhere of "rolling heads.” As such, it's notable for its "I was told" qualifier: the writer made clear that he hadn't seen the unedited ending himself; he was just quoting an anonymous source. Neither perfect understanding nor certainty was implied.

But the Censored Cartoon Page got around, and the iconic mental image of disembodied, rolling heads obviously stuck in film geeks' memories. Even the modern version of the Censored page describes the "rolling heads" scene as common knowledge, at least in the context of hearsay.

![]()

Yet there are obvious problems with it. One commonly referenced element—the dog's presence—is extra-unlikely, as the dog exits the film two full minutes before Sourpuss issues his challenge to fight. And while the goofy, Egghead-like Elmer prototype could remove his head for a gag in 1937 (

Cinderella Meets Fella), would Schlesinger animators really decapitate Sourpuss permanently—even for a scene that was nixed?

Sometimes an obvious clue is right in front of your nose. As you’ll see above, years before any reference to rolling heads, Jerry Beck and Will Friedwald referenced a less explicitly gruesome version of the final sequence in their seminal book,

The Warner Brothers Cartoons (1981). How had I forgotten that? If I wanted more details, why not simply try to watch what they’d watched?

Luckily, at least one original print of

Hare-um Scare-um still existed. I cornered and screened it recently in a film archive. Here’s what I saw.

"I can whip you and your whole family!" shouts John Sourpuss.

![]()

Bugs and his infinite family appear and put up their dukes. We hear the same musical flourish that marks the fadeout in the standard version—but there's no fade this time.

![]()

The bunnies rush Sourpuss...

![]()

...and fight in a cloud of dust. There's no sign of who's winning at first.

![]()

![]()

At the end of the battle, the bunnies rush away as one, down the road and over the horizon—visible only as a dust cloud trail.

![]()

![]()

The remaining smoke of battle clears to reveal a disheveled, but intact Sourpuss.

![]()

A critical-looking Bugs zips back onto the scene alone...

![]()

...to return Sourpuss' battered rifle to him, throwing it down on the ground hard.

Smack!![]()

Bugs (sternly): "You oughtta get that fixed. Somebody's liable to get hurt!"

![]()

His sternness vanishing, Bugs reverts to his former looney attitude.

![]()

He laughs and whoops his way down the road toward the horizon—bouncing on his head all the way, pogo-stick style.

![]()

John Sourpuss, left alone, does a long, furious slow burn...

![]()

...then snaps like a twig, and—now insane—bounces on

his head toward the horizon, too. Iris out.

![]()

How many copies of the original are out there? Surely not many; I can state with surety that Cartoon Network never aired one. On the other hand, it seems possible that some thirty years ago, when Beck and Friedwald did their original research, the news of what they'd seen got around. Maybe some cartoon fan remembered the scene in full, described it vaguely to another...

...and a statement like "they bounce over the hill on their heads" was simply misheard as the more grotesque "heads bounce over the hill." After all, the scene

was snipped from most versions of the film. If one hasn’t seen a censored moment, it’s easy to presume it must have been yanked for the ugliest reasons. Maybe that’s how the rumor got started.

Given that the scene seems non-controversial, why was the edit done? I can only make an educated guess: it’s so much like the ending of the earlier

Daffy Duck and Egghead (1938) that it comes across as completely unoriginal.

"Hold onto your seats, folks! Here we go again..."

![]() [Thanks to Jerry Beck and Mark Kausler for a lot.]

[Thanks to Jerry Beck and Mark Kausler for a lot.]

Scared yet?

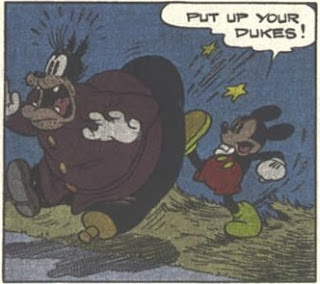

Scared yet? The great illustrations in this post come from one of the first French Disney publications—and almost certainly the first Mickey Mouse novel ever written. Scribed by Magdeleine du Genestoux and published by Librairie Hachette, Mickey et Minnie (1932) adapted the first few 1930 Mickey Mouse comics continuities to prose... lots of prose. Whole chapters go by without illustrations. But when art does appear, it’s the work of Félix Lorioux (1872-1964), a man who drew the mouse like no other.

The great illustrations in this post come from one of the first French Disney publications—and almost certainly the first Mickey Mouse novel ever written. Scribed by Magdeleine du Genestoux and published by Librairie Hachette, Mickey et Minnie (1932) adapted the first few 1930 Mickey Mouse comics continuities to prose... lots of prose. Whole chapters go by without illustrations. But when art does appear, it’s the work of Félix Lorioux (1872-1964), a man who drew the mouse like no other.

Félix Auguste Henri Marie Lorioux—his career covered in more depth elsewhere on the web—was an artist from childhood, toiling with stained glass at a local cathedral before attending a fine art school in Angers, France. Moving to Paris afterward, Lorioux designed clothing and product packaging before finding his niche in children’s books. Lorioux met Walt Disney when the latter toured France as a Red Cross ambulance driver during World War I; in some way, the connection led to Lorioux’s later employment as the first French Disney illustrator.

Félix Auguste Henri Marie Lorioux—his career covered in more depth elsewhere on the web—was an artist from childhood, toiling with stained glass at a local cathedral before attending a fine art school in Angers, France. Moving to Paris afterward, Lorioux designed clothing and product packaging before finding his niche in children’s books. Lorioux met Walt Disney when the latter toured France as a Red Cross ambulance driver during World War I; in some way, the connection led to Lorioux’s later employment as the first French Disney illustrator.

Nevertheless, Walt was apparently nonplussed by Lorioux’s abstractionist take on Mickey, Minnie, Pegleg Pete, and Sylvester Shyster. As a result, Lorioux would only work on a couple of additional Disney books. But while I can easily see the off-model aspect of Lorioux’ drawings (compare with a couple of their original comics inspirations, also pictured), I am captivated by their raw energy and enthusiasm. Shyster, with his three-day growth and butterfly-infested hat, makes me think of a refugee from a 19th century madhouse.

Nevertheless, Walt was apparently nonplussed by Lorioux’s abstractionist take on Mickey, Minnie, Pegleg Pete, and Sylvester Shyster. As a result, Lorioux would only work on a couple of additional Disney books. But while I can easily see the off-model aspect of Lorioux’ drawings (compare with a couple of their original comics inspirations, also pictured), I am captivated by their raw energy and enthusiasm. Shyster, with his three-day growth and butterfly-infested hat, makes me think of a refugee from a 19th century madhouse.