↧

Work Is Heck

↧

On With the Show (Thanks, Toby)

With the dog days of summer having passed Chihuahua and moved on to Rottweiler, my work schedule is getting a little less hectic—and some comics projects due out in the winter are finally being put to bed. So who knew? I'm back to my blog after a little too long.

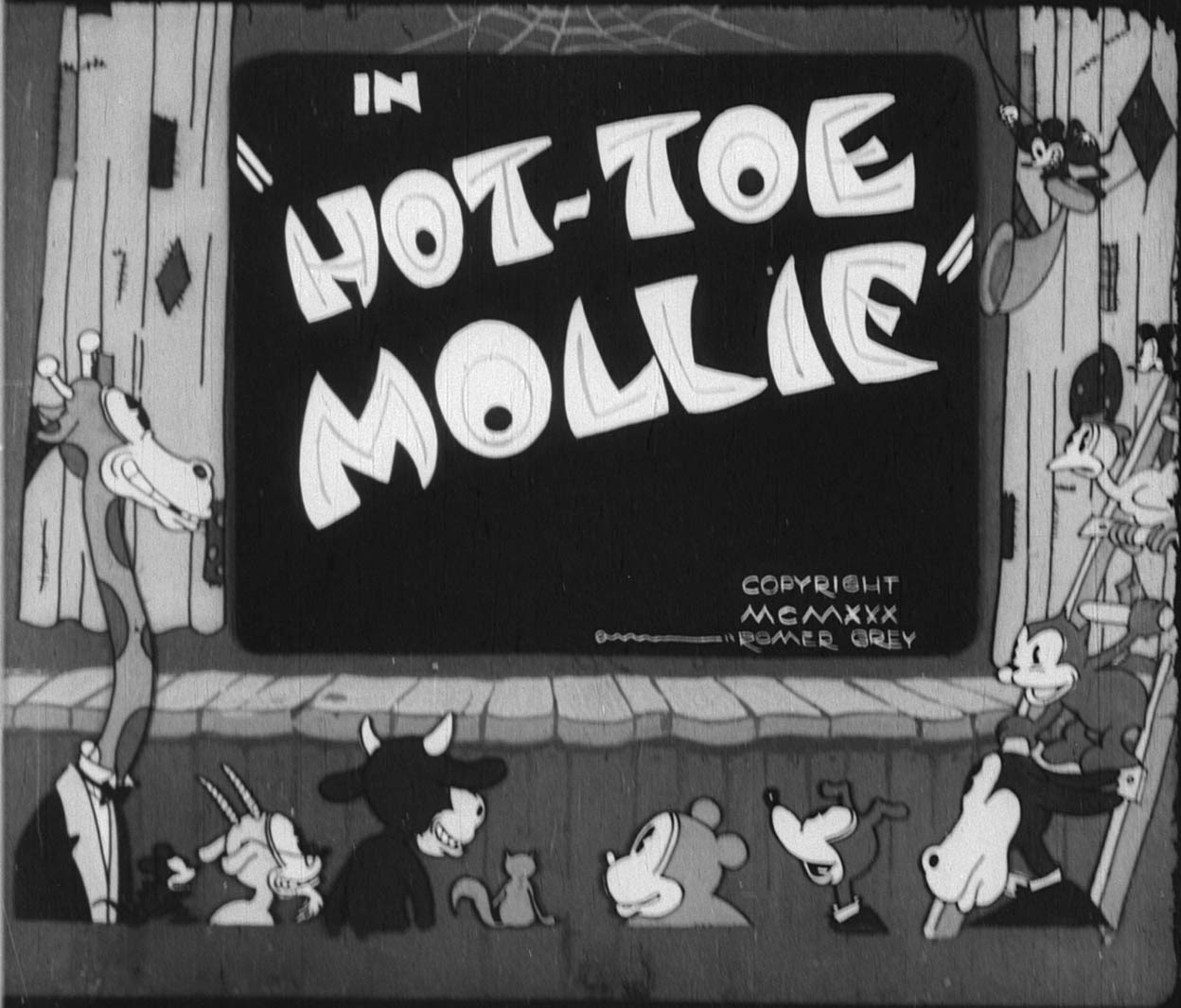

This wouldn't be Ramapith, of course, if I didn't get things moving with a rarity—and here's one so rare that it's only partly survived over the years. Carrying on the dog theme, it's Dick Huemer's Toby the Pup at his silliest. The Showman (1930) was originally a sound cartoon, but seems only to exist today as a silent print; quite a pity, as it's obviously a high-energy musical short about singing and dancing on stage. I've created the most appropriate replacement score possible by chaining together bits of other Joe De Nat Mintz scores—and a music hall tune, and one snippet from a non-Mintz score. Can you identify them?

(We're also missing some opening scenes of audiences arriving at the theatre, but I didn't have time to sit down at a light table and redraw those. Mea culpa.)

I may not be able to blog as often as I did last fall, but I'm hoping to be back before long with some more cool discoveries. Keep your fingers crossed for me... all four of them. Even if you're wearing thick white gloves.

This wouldn't be Ramapith, of course, if I didn't get things moving with a rarity—and here's one so rare that it's only partly survived over the years. Carrying on the dog theme, it's Dick Huemer's Toby the Pup at his silliest. The Showman (1930) was originally a sound cartoon, but seems only to exist today as a silent print; quite a pity, as it's obviously a high-energy musical short about singing and dancing on stage. I've created the most appropriate replacement score possible by chaining together bits of other Joe De Nat Mintz scores—and a music hall tune, and one snippet from a non-Mintz score. Can you identify them?

(We're also missing some opening scenes of audiences arriving at the theatre, but I didn't have time to sit down at a light table and redraw those. Mea culpa.)

I may not be able to blog as often as I did last fall, but I'm hoping to be back before long with some more cool discoveries. Keep your fingers crossed for me... all four of them. Even if you're wearing thick white gloves.

↧

↧

Rare Fleischer Talkartoon Found (A Shameless Plug)

Every major cartoon studio has rare and lost films to its name. Nitrate deteriorates; 16mm gets vinegar syndrome. "Duplicate" prints are cast away without careful inspection of the "master" element. Often the only source researchers know for a given title is an element that's inaccessible or unscreenable. Several Max Fleischer shorts fall into this category, preserved only in noncirculating master copies at various archives. Occasionally new prints are made from these masters. But not all the time.

Every major cartoon studio has rare and lost films to its name. Nitrate deteriorates; 16mm gets vinegar syndrome. "Duplicate" prints are cast away without careful inspection of the "master" element. Often the only source researchers know for a given title is an element that's inaccessible or unscreenable. Several Max Fleischer shorts fall into this category, preserved only in noncirculating master copies at various archives. Occasionally new prints are made from these masters. But not all the time.Luckily, new sources for rare films occasionally turn up—and with help from a few friends, I've presented several here in their entirety. Today, though, we've got a Ramapith first—a surviving rare cartoon that I'm not going to show you all of! (Hey, hold off on the rocks and socks a minute...)

Ace of Spades (1931) is a Talkartoon with a difference. Other Fleischer shorts included some soundtrack elements derived from pre-existing recordings, but this one invokes Southern and African-American vaudeville discs almost all the way from start to finish. Earlier text sources claim we're hearing the actual records on the soundtrack; as I perceive it, it's more likely that the Fleischer studio carefully re-recorded the songs and lyrics, as each has been reworded slightly to match the cartoon's poker-playing theme. "Push Them Cards Away," for example, was originally the minstrel tune "Push Dem Clouds Away" (cover by Harry C. Browne, 1917):

So why can't I show you all of Ace today?

Ace was recently acquired, in the print excerpted below, by my longtime colleague Tom Stathes—and he'll be "re-premiering" it this Friday, August 27, at "Travelaffs," the latest installment of his Cartoon Carnival screening series. If I gave the whole cartoon away, I'd be scooping him. I can, on the other hand, help plug him!

"Travelaffs" will reveal the four corners of the world as they never were: with Looney Tunes, Van Beuren, Ub Iwerks, Dick Huemer and others taking you to Italy, China, bull-infested Spain, and the politically incorrect Congo. Ace of Spades, with card sharp Bimbo out to win a poker tournament and "buy [him]self a ticket to the sunny South," fits right in with the program.

Near New York? You can fit in, too. Check out "Travelaffs," Tom Stathes Cartoon Carnival #6—where the lost will be found.

Update, August 30: We got a nice, fat turnout. Thanks a lot, friends.

↧

Lucky New Oswald Finds

As one of my favorite research topics, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit is also the subject that my longtime friends expect me to blog about most. So I generally try to keep it to a minimum—because who wants to be predictable?

As one of my favorite research topics, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit is also the subject that my longtime friends expect me to blog about most. So I generally try to keep it to a minimum—because who wants to be predictable?Of course, sometimes an unpredictable Oswald discovery is made. Then what? When it's unpredictable and Oswald-related—but David Gerstein is blogging about it—do the unpredictability and predictability cancel each other out? (And if something's not predictable or unpredictable, what is it?)

Predictable or unpredictable, you've just seen a very rare cartoon. In fact, a lot about Oswald is rare—or worse. Of the 26 Disney-made Oswald cartoons of 1927-28, Disney could locate only 13 in time for their 2007 DVD release (a fourteenth, Poor Papa, apparently exists but was inaccessible). Of the 26 Winkler Oswalds of 1928-29, only ten seem to have surfaced in modern times; and none in sound prints, though some were originally released with sound.

It's easy to guess that the all-sound Lantz Oswald package must survive in full, but you'd be wrong; Universal has master elements on most, but not all. On the other hand, collectors often assume that what's not in the general rotation must be lost; and that's wrong, too. For example, my fellow Oswald scholar, Pietro Shakarian, recently learned that our colleague Tom Klein possessed a few titles that others did not. With Tom's kind permission, we're now able to share Broadway Folly, the cartoon shown above—and Cold Feet (1930), another classic Bill Nolan-era straggler:

Thanks, Tom! (Tom, by the way, is the author of "Walt-to-Walt Oswald" [Griffithiana 71, 2001], a seminal paper on the character's early days—crucial reading.)

So which Lantz Oswald cartoons are still MIA? Here's what Pietro and I believe to be a definitive list—with summaries based on the original copyright synopses. Anyone want to help us find these?

Cold Turkey (released 10/15/29; production number 5043, © MP 728)

Synopsis: Taking time off the job to dance with his "best girl," waiter Oswald is interrupted by an irate customer who wants an order of duck for dinner. Oswald obliges, but the duck resists death by decapitation and hanging. Oswald finally solves the situation by shooting the duck with a cannon, leaving it "done to a turn—and well roasted." Oswald: "Want some?" Girl: "I bite!"

Note: If the synopsis is accurate regarding dialogue, this would seem to be the first Lantz cartoon with spoken words (during this period, Lantz and his crew otherwise largely relied on a slide whistle to perform Oswald's voice).

Pussy Willie (released 10/28/29; production number 5063, © MP 758)

Synopsis: Oswald heads to his girlfriend's house and is faced with the problem of her "kid brother," who gives Oswald no end of trouble. Willie's misdeeds include putting pepper in the flowers that Oswald gives his girl. Fed up, Oswald throws "the imp off a dock." The kid returns and finds Oswald and his girl—desperate for privacy—locked in a safe. Willie uses TNT to blast them to Heaven—and comes along with them to slam the pearly gates in their faces.

Note: We're presuming "Pussy Willie" is the same bratty little cat who debuts in Disney's All Wet (1927)—then reappears as Homeless Homer in the eponymous Winkler title (1928), and once again as the girlfriend's kid brother in Lantz's The Fireman (1931). Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising reused him at Warner as Bosko's foil, renaming him "Wilbur"; you have to wonder if Oswald paid Bosko to take him.Nutty Notes (released 12/9/29; production number 5062, © MP 855)

Synopsis: When Oswald gets a new job at a music store, his "bruin" boss tasks him with hoisting a piano to "Ozzie's girl's" apartment—on the top floor of a skyscraper! After several efforts fail, Oswald tricks a goat into kicking the piano upward, but the kick is delivered with "too much English," and the hurtling piano rips the roof off the building. Upon Oswald's descent, he is united with his girl and the two kiss happily.

Note: The poster survives, as illustrated at right. While the copyright description calls Oswald's boss a bear, the poster pictures a cat.

Ozzie of the Circus (released 12/23/29; production number 5024, © MP 938)

Synopsis: Oswald spends a day at the circus where he runs into a smart-aleck pup. The dog trips the barker, causes problems for the "two-headed sax player," and ties Oswald's tail to a strength-test indicator. After getting loose, Oswald chases the pup but soon finds himself pursued by an angry gorilla. The chase goes on and on; carrying over to the closing title, where "we leave them hotfooting it around the Universal universe—a dangerous triangle going around in circles!"

Note: Erroneously thought to be the first-released Lantz Oswald short until research in 2005 proved otherwise.

Kisses and Kurses (released 2/17/30; production number 5127, © MP 1147)

Synopsis: Oswald is part of a showboat troupe, with his girlfriend Fanny as leading lady in a melodrama. "Little Blue Eyes, the heroine, live[s] with her aged father in a wee cabin down on the Swanee. Simon Hardheart [played by Pete] demand[s] her hand in marriage, but Blue Eyes spurn[s] him. In fury, Simon tie[s] her to a railroad track and vows to run over her with an old locomotive called The General." She is rescued by Oswald, who splits the track—and by extension, the train and villain—in half! The show is a success and Oswald and Fanny embrace for the closer.

Note: The General got its name compliments, no doubt, of Buster Keaton!

Bowery Bimboes (released 3/18/30; production number 5154, © LP 1162)

Synopsis: Oswald is a cop on the beat in the Bowery. A girl catches his eye and the two engage in a rough Apache dance. But the girl is kidnapped by a tough-guy rat who spirits her to a skyscraper and hoists her to the top. Oswald comes to the rescue with an extension ladder; he saves her, but the ladder breaks. The two end up falling to the ground—but revive in time for a closing kiss.

Note: It seems likely to us that the tough-guy rat is the one who's also in The Prison Panic (1930). While the picture element for Bowery Bimboes is presently lost, an original soundtrack disc survives in my personal collection. Thanks to Ron Hutchinson's tech support, I'm honored to present it to you here:

Hey, that's not the end of the Ramapith audio selection for today. I'd be remiss if I didn't share Billy Murray's and Aileen Stanley's priceless performance of "Down By the Winegar Woiks" (1925), the song that you (appropriately) heard over Bowery Bimboes' opening titles:

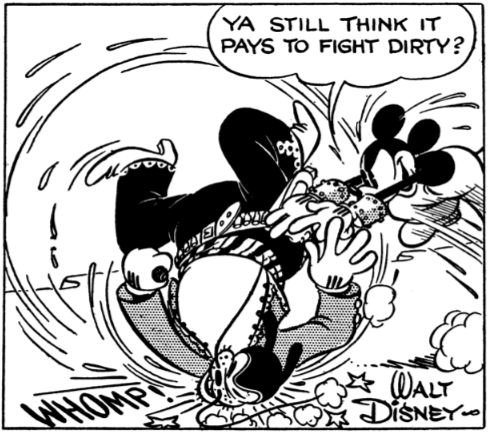

And how about "Hi-Lee, Hi-Lo," as heard in Cold Feet? This one is all over 1930s cartoons—Donald Duck sings it in On Ice (1935), and it even survives as his theme in a couple of period comics (example at right from 1936 Sunday page: story by Ted Osborne, art by Al Taliaferro). Here's George P. Watson covering it in 1909:

And how about "Hi-Lee, Hi-Lo," as heard in Cold Feet? This one is all over 1930s cartoons—Donald Duck sings it in On Ice (1935), and it even survives as his theme in a couple of period comics (example at right from 1936 Sunday page: story by Ted Osborne, art by Al Taliaferro). Here's George P. Watson covering it in 1909:Pietro, meanwhile, has caught studio musician David Broekman enlivening Broadway Folly with "Hittin' the Ceiling," a tune from Universal's rare part-Technicolor musical Broadway (1929). Carrying on in the same spirit, Broekman colleague Bert Fiske used the Broadway number "Sing a Little Love Song" for the marriage-proposal scene of Oswald's Oil's Well (1929; see sequence starting at 1:53).

I'd be remiss not to mention Pietro's contributions to Golden Age Cartoons' Walter Lantz Cartune Encyclopedia, where he informs me he's just now adding our new Oswald discoveries to the 1929 and 1930 pages. Hop on over, rabbit-style, to read more about them.

Update, September 3: I'd be remiss, too, not to link us to the first new Disney animation of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit in 82 years. Nope, it's not what some of you would have expected...

Update, September 3: I'd be remiss, too, not to link us to the first new Disney animation of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit in 82 years. Nope, it's not what some of you would have expected...

↧

Fantastic Felix Friday! Watch this space...

Big, big doings here on Ramapith later today; fans of Otto Messmer, Joe Oriolo, and Jim Tyer have been warned (and that goes for fans of Inky, Winky, and highly suspect magic carpets and bags, too).

Big, big doings here on Ramapith later today; fans of Otto Messmer, Joe Oriolo, and Jim Tyer have been warned (and that goes for fans of Inky, Winky, and highly suspect magic carpets and bags, too).In the meantime, while we're getting ready, feel free to refresh yourself with our Felix 90th birthday tribute from last fall. (Has it really been that long?) Or check out the other blogs which we've joined today to create a Felix maelstrom of mirth:

http://www.cartoonsnap.com/

http://thehorrorsofitall.blogspot.com/

http://andeverythingelsetoo.blogspot.com/

http://www.fourcolorshadows.blogspot.com/

http://www.comicbookbin.com/Beth_Davies-Stofka.html

http://www.comicrazys.com/

http://www.theitchblog.com/

(Image © Felix the Cat Productions, all rights reserved)

↧

↧

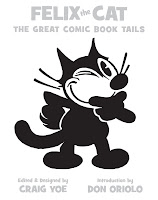

Fantastic Felix Friday: Behind the Scenes

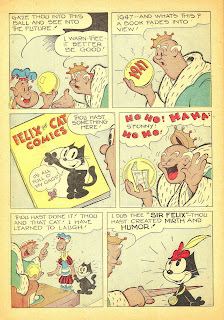

Rowr! It's been awhile since Felix the Cat prowled Ramapith's ivy-covered halls. But the feisty feline always comes back. This week I'm honored to help promote him in a new project for which I was a consulting researcher: Craig Yoe's and Don Oriolo's Felix the Cat: The Great Comic Book Tails. We're all calling today "Fantastic Felix Friday" and many of us collaborators are blogging about the book—time to do my bit.

Rowr! It's been awhile since Felix the Cat prowled Ramapith's ivy-covered halls. But the feisty feline always comes back. This week I'm honored to help promote him in a new project for which I was a consulting researcher: Craig Yoe's and Don Oriolo's Felix the Cat: The Great Comic Book Tails. We're all calling today "Fantastic Felix Friday" and many of us collaborators are blogging about the book—time to do my bit. Lots of us know Felix from his classic cartoons—both the vintage Otto Messmer head-trips of the 1920s and the famous Joe Oriolo Professor/Rock Bottom battles of the 1950s. Many of us know Felix's comic strip exploits, too—in which Otto and Joe again played central roles, drawing blissful dailies and Sundays for many a decade. But there's never been a really solid collection of Felix's comic book adventures. However—the times, they are a-changing! Thanks to both the Oriolo company archives and various collectors' holdings, Craig and Don (son of Joe) have put together this lavish, in-depth look at the first ten years of Felix made for magazines.

Lots of us know Felix from his classic cartoons—both the vintage Otto Messmer head-trips of the 1920s and the famous Joe Oriolo Professor/Rock Bottom battles of the 1950s. Many of us know Felix's comic strip exploits, too—in which Otto and Joe again played central roles, drawing blissful dailies and Sundays for many a decade. But there's never been a really solid collection of Felix's comic book adventures. However—the times, they are a-changing! Thanks to both the Oriolo company archives and various collectors' holdings, Craig and Don (son of Joe) have put together this lavish, in-depth look at the first ten years of Felix made for magazines. When Felix's original comic book stories kicked off in 1946, he wasn't quite the same cat that he'd been twenty years earlier on-screen. His catty resourcefulness remained, but in other ways he had become more human than feline. Felix lived in a house now; paid his bills (or tried to!) and generally coexisted with people as a peer, not a pet.

When Felix's original comic book stories kicked off in 1946, he wasn't quite the same cat that he'd been twenty years earlier on-screen. His catty resourcefulness remained, but in other ways he had become more human than feline. Felix lived in a house now; paid his bills (or tried to!) and generally coexisted with people as a peer, not a pet.But if Felix's animal nature had declined, his propensity for fantasy was wilder and woolier than ever before. This was the Felix who not only visited Toyland and various Oz-like domains—but permanently owned a magic carpet, enabling him to go back to them again and again. This was the Felix who discovered that when you cooked vegetables, giant vegetables would one day catch you and try to cook you, too.

Eyes downward, readers, and you'll find "Starbust" (Four Color 135, 1946), the opening story in the new book. Dig that Art Deco star on Page 1—and don't you just love how this actually becomes a story about escaping the star? Nobody but Felix got into adventures this wacky. Nobody else dared.

Eyes downward, readers, and you'll find "Starbust" (Four Color 135, 1946), the opening story in the new book. Dig that Art Deco star on Page 1—and don't you just love how this actually becomes a story about escaping the star? Nobody but Felix got into adventures this wacky. Nobody else dared.Pages 1, 2, 4, 6, and 9-16 appear to me to be drawn by Otto Messmer, with inks mostly by Messmer but sometimes by Joe Oriolo (the extra-wide cut in Felix's pie-eye on Page 4, Pic 2 suggests Oriolo in this period, as do images of Felix with a round back to his head rather than the usual cowlick).

Pages 3 and 5 are by Jim Tyer—dig the classic Tyer bum and sheriff designs!—and 7 and 8 appear to me to be Messmer and Tyer working together.

But let's see what you think. Then join me after the jump for an even more special Felician feature... (Comic © Felix the Cat Productions, all rights reserved.)

Welcome back. (Nice comic, huh?) I've got Don Oriolo with me today—son of Joe, Don began life scampering around his dad's and "Uncle Otto's" drawing boards; not a bad place to start out! I thought I'd interview Don for "Fantastic Felix Friday" to get some inside dope about the stories in Great Comic Book Tails—and about some other long-simmering Felix mysteries.

I'll switch to boldface for proper interview technique and let's get going!

Glad to have you here, Don! Hm, where to begin? Most Felix comic book stories were drawn by Otto Messmer and your dad, Joe Oriolo. But for the first couple of years at Dell, super-screwy cartoonist Jim Tyer—best known for his distinctive, outrageous style at Terrytoons and Fleischer—was also a contributor. Did you meet Tyer when he worked with your dad? Did Joe or Otto have any special memories of him?

Hi, David... first of all, let me say it's always a pleasure to talk with you, and I'm continuously amazed at your knowledge of all things Felix. Yes; Jim, or Mr. Tyer as I called him, was one of the Fleischer guys that my father and Otto worked with during those wondrous Fleischer and Famous Studios days. My father loved to have barbecues, and the Fleischer "family" was always there. I know both my father and Otto admired Jim's talent. Jim also worked on a couple of Trans-Lux [Felix TV] episodes.The Felix stories in this book come from a transitional period when Felix's supporting cast was changing. We see Flub the dog, Inky and Winky, and Pokey the pig, but only in relatively brief parts. On the other hand, we also get a brief cameo from a crook who's clearly a Rock Bottom ancestor (in the story "Seeds and Proceeds"). When your dad added Rock and the Professor to the cast, how did it come about? They were almost never in the comics, so did Trans-Lux request that the cast be filled out especially for TV?

That's exactly how it happened. Trans Lux wanted more ancillary characters... so my father reached back to Butch who became Rock Bottom.

You mean Butch the bully from the 1950s-era newspaper strips, right?

Yes. Butch was sort of a predecessor of Rock... minor changes, of course. "Rock Bottom" was a name that just popped out of my father's head; a typical punnish play on words that the Popeye guys always toyed with. Poindexter was the last name of my father's lawyer, Emmett Poindexter. Pokey the pig was also called Starvin' Marvin...

The Professor was an an amalgam of various "professorial" characters that appeared in the comics and strips through the years. I think one of the most brilliant off-the-cuff design concepts was the button on Poindexter's lab coat... I always asked my father what that button did, and I always got the runaround. I think he only used it a couple of times in the series.Many of the Great Comic Book Tails show Felix with his Magic Carpet—and a very unmagic travel bag. Your dad made the decision to combine them, creating the famous Magic Bag. But had the Carpet been your dad's creation too? What motivated the decision to change two into one?

Yes, it was my father's. My father was fascinated with the Arabian Nights and The Thief of Bagdad (1940). He would always tell me, my brother and sister stories of flying carpets and time machines. I was always imagining that one of the Persian rugs in our house could fly me anywhere in the universe—and in my playtime imagination, it did. The Magic Bag was an element created to give an easy way out in the five-minute [TV] episodes... it replaced the piercing of the fourth wall in simpler terms for a series with such a limited budget.

Felix's Carpet was this big, clunky looking thing...

It was the way both my dad and Otto drew rugs—tassels and all. Those guys never thought about taking the easy way out when they were doing the strips or comic books. They always went the extra mile with the backgrounds.Fairy tales and fantastic travel are a recurring theme in these Felix comics adventures—gotta love the kingdom of Vegeteria and the other kooky places Felix visits. Did your dad or "Uncle Otto" ever tell you why this theme became so crucial for Felix? Was any inspiration from L. Frank Baum (Oz) or Johnny Gruelle (Raggedy Ann) involved? Your dad worked on Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy (1941) at Fleischer [illustration at left]...

Raggedy Ann was loved by both my dad and Otto. My dad also eventually did lots of design work for Joe Raposo of Sesame Street fame [songwriter for Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure (1976)]. Otto drew a mean Raggedy Ann, also. The Fleischer theory was that everything was alive... even vegetables danced along with the streetlamps and talking doorknobs. My father read everything Baum ever wrote. I wish I still had those old books.Speaking of fantastic travel, your dad introduced Vavoom, the noisy little Inuit who was a spiritual successor to many of the earlier eccentric characters Felix had met on his travels. Can you tell me a little about how Vavoom originated?

I had a little drawing board next to my father... I was home sick one day from school, and as my father was doing the daily Felix strip, I sneezed. He flew off his chair. I thought "Wow, I have a powerful magic sneeze!" So I "force-sneezed" at my father who flew backwards, and stumbled down the stairs as I continued to "sneeze" at him. Not long after that he designed a character loosely called Sneezy. When they were deciding on the cast of the Felix TV series, he brought that character up; Trans-Lux liked the character, but said "You can't have him promote unhealthy, sickly behavior!" After which my father changed his name to Vavoom, after the Jackie Gleason phrase—va-va-va-voom!

For years, Felix studio founder Pat Sullivan claimed to have created Felix. Later, his estate continued to control the character—and as long as they did, Sullivan continued to get the credit. I'm not going to get into the issue of Felix's creation right now—but we both know Messmer might never have gotten any due had your dad not acquired permanent Felix rights from Sullivan's heirs. How did this come about?

Pat Sullivan, the nephew [of studio founder Pat Sullivan] traded 50% of the stock to my father for his creating and selling the pilot of the Trans-Lux Felix TV series. I bought all of the remaining stock from the stockholders through the years.

Speaking of the TV series, it's time for one of those existential questions. Sometimes the Professor is Felix's sworn enemy, battling with him for Magic Bag possession. But at other times, the Professor is Felix's boss, hiring him as lab help or to babysit Poindexter. How did your Dad explain the Professor's varying roles as bad guy and good guy?It's sort of the same concept as Bluto being friendly to Popeye in a couple of episodes. It just happened by way of scripts that were churned out in hours. Don't forget they were doing a few episodes a week. They didn't overthink anything or analyze anything because there was nothing to analyze. They were creating what is our history now—and didn't think of the ramifications!

In the 1950s, Felix's nephews Inky and Winky became especially popular for awhile, even getting a comic book of their own. But as longtime Felix fans know, the kittens have an oddity attached to them. The comics called them Inky and Dinky; the merchandise called them Inky and Winky, especially later on. Can you tell us why this was?My father just liked the name Winky better... and the word "dinky" had a connotation of being insignificant at the time; it didn't sound positive to my father. I remember his having that conversation with me as a child.

Felix is a bit of a rascal—known to nab the occasional fish or down the occasional martini. It's part of what makes him human. But in the 1950s, for awhile we saw less of this. What restrictions did Trans-Lux put on Felix's mischief?

They wanted a "younger" show. That's why Jack Mercer [voice of Felix and all other male characters on the show] spoke in slow deliberate tones. Felix was to be everybody's best friend—who could solve any problem anyone had, even if it meant taking the easy way out with the Magic Bag.One more newspaper strip question. For awhile in the 1940s, Messmer's Felix daily featured nothing but battles between Felix and Skiddoo the mouse—day-in, day-out. Did Messmer or Oriolo ever tell you why the strip went through this period? Did it have to do with King Features' decisions?

A lot of the writing on those strips were off the cuff mental streaming of Otto and my dad. Mice worked with cats—and Farmer Gray!—so why not with Felix? It was a way of getting a running gag in a time when they were expected to churn out a script a day.

Some stories in Felix the Cat: The Great Comic Book Tails come from Dell Comics editions; others come from Toby Press, which took over publication in 1951. Why did Felix make the move from Dell to Toby?

I think Dell was winding down with their commitment to publish the Felix comics and Toby was very, very interested in carrying on. I personally really like the Toby Press days—though it was one almost-interchangeable comics community as I saw it as a kid. My father was always going to one or all of the offices on a weekly basis. I was happy because he always came home with a bag full of comics. I was like a pig in—well, you know what I mean. I was a very happy kid!

And I've been very happy to have you here, Don!

That almost wraps up our Felix goodies for today—but not quite! This wouldn't be a Ramapith blogpost without an extra-esoteric turn-of-the-century pop tune. In the earlier-referenced Greatest Comic Book Tails story "Seeds and Proceeds," vegetable-grower Felix discovers super seeds that create incredible plant growth. "Burbank should see this," Felix grins. Huh? This unusual pop culture ref is a shout-out to Luther Burbank (1849-1926), pioneer horticulturalist—a man who may be little-remembered by the general public today, but to whom every gourmet and naturalist owes a debt of gratitude.

That almost wraps up our Felix goodies for today—but not quite! This wouldn't be a Ramapith blogpost without an extra-esoteric turn-of-the-century pop tune. In the earlier-referenced Greatest Comic Book Tails story "Seeds and Proceeds," vegetable-grower Felix discovers super seeds that create incredible plant growth. "Burbank should see this," Felix grins. Huh? This unusual pop culture ref is a shout-out to Luther Burbank (1849-1926), pioneer horticulturalist—a man who may be little-remembered by the general public today, but to whom every gourmet and naturalist owes a debt of gratitude.Let's finish things off with "Burbank the Wizard" (1911), an earlier tribute to "the world's greatest farmer" by singer/comedian Murray K. Hill...

And don't forget to visit the other Fantastic Felix Friday bloggers! We've all joined together today to create a web-wide Felix maelstrom of mirth:

http://andeverythingelsetoo.blogspot.com/

http://www.cartoonsnap.com/

http://www.comicbookbin.com/

http://www.comicrazys.com/

http://www.fourcolorshadows.blogspot.com/

http://itsthecat.com/blog

http://thehorrorsofitall.blogspot.com/

http://www.theitchblog.com/

↧

Mystical Felix Monday: There's More?

Hey, who said it was over? At the time our Fantastic Felix Friday celebration finished up last week, an e-mail snafu had unknowingly kept me from receiving Don Oriolo's replies for two extra Felix the Cat interview questions. But the Cat always comes back—and now Don is back, too, with one of the funniest Felix anecdotes ever. All in service, of course, to Felix the Cat: The Great Comic Book Tails, Don's new book with Yoe! Studio—an exciting collection of Otto Messmer, Joe Oriolo, and Jim Tyer Felix adventures that's available now.

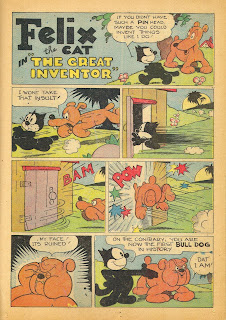

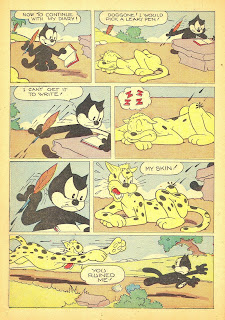

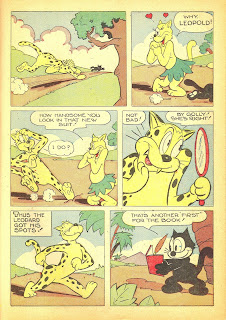

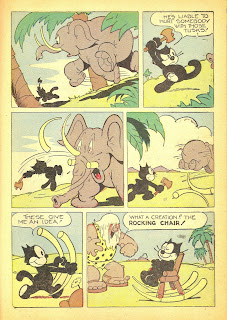

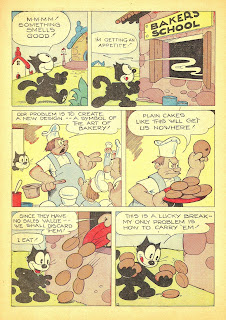

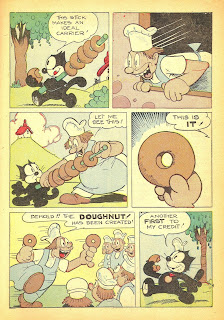

Hey, who said it was over? At the time our Fantastic Felix Friday celebration finished up last week, an e-mail snafu had unknowingly kept me from receiving Don Oriolo's replies for two extra Felix the Cat interview questions. But the Cat always comes back—and now Don is back, too, with one of the funniest Felix anecdotes ever. All in service, of course, to Felix the Cat: The Great Comic Book Tails, Don's new book with Yoe! Studio—an exciting collection of Otto Messmer, Joe Oriolo, and Jim Tyer Felix adventures that's available now. What, you want another adventure here? Oh, all right. But I don't want to spoil too much. So following below is "The Great Inventor" (Four Color 135, 1946), a Felix story that's not in Great Comic Book Tails. While I don't want to state the credits with certainty, I believe pages 1-13 are largely by Otto Messmer, with inks by Otto, Joe Oriolo and possibly Jack Bogle (pages 4 and 5). Pages 14-16 are—I believe—penciled by Jim Tyer and inked by Joe.

What, you want another adventure here? Oh, all right. But I don't want to spoil too much. So following below is "The Great Inventor" (Four Color 135, 1946), a Felix story that's not in Great Comic Book Tails. While I don't want to state the credits with certainty, I believe pages 1-13 are largely by Otto Messmer, with inks by Otto, Joe Oriolo and possibly Jack Bogle (pages 4 and 5). Pages 14-16 are—I believe—penciled by Jim Tyer and inked by Joe.(Comic © Felix the Cat Productions; all rights reserved.)

And now I'm back with Don for those final two questions—switching to boldface interview style now!

Don, the stories in Great Comic Book Tails seem almost to be trying to top each other for wildest adventure or most outrageous fantasy scenario. What's your own favorite from among those stories? And what would you say was your dad's most outrageous Felix cartoon story?I love "Felix Pulls Through" (Felix the Cat 13, 1950)! I remember my father penciling and inking it like it was yesterday... I was fascinated when Felix threw the magnetic ore into the air and the cannonballs and weaponry were attracted to it, thereby veering away from Felix. I totally remember when my father drew the cluster of cannonballs all stuck together; I watched with baited breath as he inked it, and I could see it coming to life. As soon as he inked around the little reflective windows that he left white, the whole scene popped; that stuck in my head to this day! That's how I ink reflections, too.

Regarding Felix animated on the screen, I loved Master Cylinder, King of the Moon (1959)—when Master Cylinder established himself as king, it was so bizarre; that a character named after the working business of an auto brake system was crowned king of the moon. Why? I had these battles with my father all the time. His answer was, "Why not?"

So what was the most outrageous situation Felix ever got you into? These things tend to happen when he crosses our paths.

Well, it's funny you should mention that, David. About 12 years ago (seems like yesterday!) my mother got involved in investing in an "amusement" park in Palm City, Florida. The object was to have more "intellectual" exhibits for children—and to do away with traditional amusement rides, et cetera. It was more like an outdoor library than an amusement park!

And the whole construction of the park was running years over schedule; it was not looking good. Well, one of the things that my mother donated—along with the usual bricks with family members' names etched into them—was a version of "Where's Waldo?"... or rather "Where's Felix?" Yup, you heard it... I designed—and the park council produced—seven solid brass Felix statues, painted black and white. They were amazingly heavy and each one stood about three feet tall. They were actually pretty cool... but by the time they were ready, I was getting very skeptical about the plan. The principals in the park, called "Gift Gardens" after someone named Gift, were constantly bickering and replacing each other with even less efficient people. You have to understand that they actually built this thing. It was probably about 10 to 15 acres with a brand new high masonry wall around the whole bit.The park opened without fanfare; and as I walked past the "Where's Felix" section—a nicely landscaped plot of land about thirty feet square—and looked around, I saw no press; just a handful of people and a bunch of bizarre exhibits. Whatever kids were there walked along the path with glazed looks on their faces. "Where are the rides?" I said to myself. "This does not look good."

To make a long story short: the park opened one day, and was locked tighter than a sardine can the next day! I was like, "What the heck?" It started with good intentions, but was built by do-gooders raising money from local retired people, and it also felt like maybe they did it as some kind of tax shelter scam. I was livid. I went back that afternoon and there was already graffiti on the beautiful eight-foot wall. "Okay," I said, "this confirms my suspicions; this park is going to be looted and destroyed in a matter of days." No security... it was completely abandoned.

I thought back; how would Errol Flynn get over this wall in Robin Hood? Oh, yeah... there's a ladder over there...

You saved the statues.

Yeah, you got it; I climbed over the wall, and I carried those ridiculously heavy statues from one side of the park to the front wall. One by one I placed the rescued Felix statues on the top of the wall. I was exhausted... but these were our Felix statues; we paid for them plus plus plus... and the park owners had abandoned the place. I was upset to say the least.

In any event, today those statues live in my studio and the homes of a couple of my nephews. Boy, the things we do for that Wonderful Wonderful Cat!

I'll say! Truth is stranger than fiction.

Glad to have you h— uh, glad to have you here again, Don. And speaking of strangeness; to finish off this blogpost in style, it's time to share a true Felix oddity with readers. Dating from 1924, "Since Felix Has Been Shingled" was among the earliest Felix spinoff tunes; and is rare enough that until very recently, I wasn't aware it had been recorded.

Glad to have you h— uh, glad to have you here again, Don. And speaking of strangeness; to finish off this blogpost in style, it's time to share a true Felix oddity with readers. Dating from 1924, "Since Felix Has Been Shingled" was among the earliest Felix spinoff tunes; and is rare enough that until very recently, I wasn't aware it had been recorded.But times change. Rarities are rediscovered. And now—thanks to collector David Moore—here's England's own Clarkson Rose with the story of our favorite cat... being forced to get a lady's hairdo. Maybe fiction is stranger.

Felix has been walking since the day that he was bornDon't forget to visit my sister (brother?) blogs from last week's Fantastic Felix Friday:

And so to keep him home at nights we had to have him shorn;

We did not like to 'bob' him; he didn't look the part;

So we went and had him shingled and it nearly broke his heart.

Now Felix is shingled he won't go out of doors;

He lies on a cushion and snores, and snores, and snores.

He's canceled engagements which he'd made by the score

Since Felix has been shingled he won't walk anymore.

Felix caused great jealousy amongst the other Toms,

But since he has been shingled now, they wag their to's and froms.

He rivals them no longer among the lady cats;

He never spends his ev'nings now in other people's flats.

Now Felix is shingled he won't go out of doors;

He won't trim his whiskers, he's left off his plus fours;

The Sheik of the Tabbies in the good old days of yore

Since Felix has been shingled he won't sheik anymore.

Felix rivaled Owen Nares when he made his bow

But Felix now is owing hairs; meow! meow! meow!

http://andeverythingelsetoo.blogspot.com/

http://www.cartoonsnap.com/

http://www.comicbookbin.com/

http://www.comicrazys.com/

http://www.fourcolorshadows.blogspot.com/

http://itsthecat.com/blog

http://thehorrorsofitall.blogspot.com/

http://www.theitchblog.com/

Thanks Craig, and thanks Don!

↧

Lost Laugh-O-Grams Found—And Shown

"Alice isn't Alice." Those three words recently marked the start of an exciting series of discoveries for me and others. But what could they mean?

"Alice isn't Alice." Those three words recently marked the start of an exciting series of discoveries for me and others. But what could they mean?Like a lot of cartoon researchers, I've long been disappointed that more of Walt Disney's 1920s Kansas City animation didn't seem to survive. Recently, though, colleagues and I have turned up some exciting discoveries—some of which, I'm pleased to announce, are about to reach public eyes after a long, long absence.

First, a bit of background. Until recently, it was believed that only four of Disney's Laugh-O-Grams fairy tale cartoons still existed: Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots, Cinderella, and The Four Musicians of Bremen (all 1922). It was also conventional wisdom that the fairy tales had been a series of six, released only in the United States—and perhaps only in part; for soon after buying the series from Disney, non-theatrical distributor Pictorial Clubs of Tennessee filed for bankruptcy.

But Pictorial Clubs had shady sister companies in different states. Some, it turns out, continued to distribute Laugh-O-Grams years later; all seven of them, not six. Jack and the Beanstalk and Jack the Giant Killer (both 1922), two titles traditionally misremembered as one and the same, were actually different shorts. A 1922 press release, discovered by researcher Michael Barrier, announced that the series would include both titles; John Kenworthy noted the two titles listed as separate, completed cartoons among Laugh-O-Gram Films' bankruptcy records.

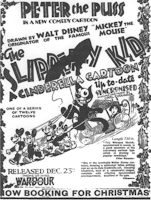

As the sound era dawned, the seven fairy tales changed owners. As early as 1991, J. P. Storm and M. Dreßler's pivotal German study Im Reich der Micky Maus included German release information for a 1929 Disney cartoon series entitled "Wuppy"; in his Animated Film Encyclopedia (2000), Graham Webb revealed an American equivalent alternately titled "Whoopee Sketches" and "Peter the Puss." Bollman and Grant were credited as producers for the New York-based Sound Film Distributing Corp.; in England, Wardour Films distributed the reels theatrically.

As the sound era dawned, the seven fairy tales changed owners. As early as 1991, J. P. Storm and M. Dreßler's pivotal German study Im Reich der Micky Maus included German release information for a 1929 Disney cartoon series entitled "Wuppy"; in his Animated Film Encyclopedia (2000), Graham Webb revealed an American equivalent alternately titled "Whoopee Sketches" and "Peter the Puss." Bollman and Grant were credited as producers for the New York-based Sound Film Distributing Corp.; in England, Wardour Films distributed the reels theatrically. Webb was the first to verify that these Whoopee/Peter titles were Laugh-O-Grams retrofitted with soundtracks—with "Peter the Puss" being a new name for Disney's Julius the Cat (or his Laugh-O-Gram prototype). The Whoopee/Peter title "Grandma Steps Out" turned up in the collection of David Wyatt, and was clearly Disney's Little Red Riding Hood. Webb tagged Disney's Cinderella (1922) as the Whoopee/Peter "The Slipper-y Kid," Goldie Locks and the Three Bears (1922) as "The Peroxide Kid," and Puss in Boots as "The K-O Kid."

Webb was the first to verify that these Whoopee/Peter titles were Laugh-O-Grams retrofitted with soundtracks—with "Peter the Puss" being a new name for Disney's Julius the Cat (or his Laugh-O-Gram prototype). The Whoopee/Peter title "Grandma Steps Out" turned up in the collection of David Wyatt, and was clearly Disney's Little Red Riding Hood. Webb tagged Disney's Cinderella (1922) as the Whoopee/Peter "The Slipper-y Kid," Goldie Locks and the Three Bears (1922) as "The Peroxide Kid," and Puss in Boots as "The K-O Kid."But there were more Whoopee/Peter titles than there were Laugh-O-Gram fairy tales. Some records suggested 12 Whoopee cartoons were released; nine made it to Germany, and Storm/Dreßler and Webb collectively found title listings for ten. Would we ever actually see the films to conclusively identify them all?

"Alice isn't Alice." In 2005, researcher Cole Johnson told me about having screened a misidentified cartoon at the Museum of Modern Art. Though tagged as Disney's Alice and the Three Bears (1924)—as it had been since its acquisition, decades before—this cartoon didn't feature a live-action Alice, as was SOP for the Alice Comedies. Instead Alice was animated. Or was it Alice? Cole believed we were seeing Goldie Locks, and the print title, "The Peroxide Kid," guaranteed it. Exceptional find, Cole.

Where one retitled print existed, might there be more? Sure enough. In time, MoMA proved to possess other previously unprovenanced reels that, when inspected, revealed Whoopee and/or Peter main titles. Now the discoveries, and confirmed identifications, flew thick and fast. Two Whoopee Sketches, "Rural Romeo" and "Egg-Splosion," turned out not to be Disney shorts. As for those that were, we already knew "Grandma" was Red Riding Hood and "Peroxide" Goldie Locks; now "The Four Jazz Boys" was confirmed as Bremen, while helpful MoMA staffers found for me that "The Cat's Whiskers" matched Disney's Puss in Boots.

Of course, if "Whiskers" was Boots, then Webb had been incorrect with one title assignment. What was "The K-O Kid"? MoMA had a film element bearing that title, but it was not screenable when I did my initial research last fall. Luckily, a 1969 MoMA plot synopsis survived—and matched up point for point with a 1924 review of Jack the Giant Killer (above), which I'd located in The Educational Screen non-theatrical exhibitors' magazine. Shortly after, another print also turned up at MoMA; now elements of both have been combined and Giant Killer properly restored and preserved.

Of course, if "Whiskers" was Boots, then Webb had been incorrect with one title assignment. What was "The K-O Kid"? MoMA had a film element bearing that title, but it was not screenable when I did my initial research last fall. Luckily, a 1969 MoMA plot synopsis survived—and matched up point for point with a 1924 review of Jack the Giant Killer (above), which I'd located in The Educational Screen non-theatrical exhibitors' magazine. Shortly after, another print also turned up at MoMA; now elements of both have been combined and Giant Killer properly restored and preserved. In the shuffle, one might have forgotten Jack and the Beanstalk, on which no element has yet turned up at MoMA. With luck, however, I did locate an element in a private collection last spring; once again under its Peter the Puss title, "On the Up and Up." Thus all seven Laugh-O-Gram fairy tales have now been found.

In the shuffle, one might have forgotten Jack and the Beanstalk, on which no element has yet turned up at MoMA. With luck, however, I did locate an element in a private collection last spring; once again under its Peter the Puss title, "On the Up and Up." Thus all seven Laugh-O-Gram fairy tales have now been found.Want to see some? Sure you do. And that leads me to more good news—some will be screened, and soon. This October 31 will bring us a Halloween treat: longtime silent film scholar and fellow cartoon researcher, Serge Bromberg, is coming from Europe for MoMA's annual To Save and Project festival, and he'll be presenting a special Laugh-O-Grams program. Along with now-preserved prints of Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots, and Four Musicians of Bremen, the newly discovered Jack the Giant Killer and Goldie Locks and the Three Bears will also be shown. Serge will provide his usual stellar background info and piano accompaniment. And as icing on the cake, later Ub Iwerks cartoons will also be at the screening, including Flip the Frog's Techno-Cracked (1933) and my personal favorite, Don Quixote (1934).

Can't make it on the 31st? Come on November 4. This is one time when cartoon research has gotten great results—for Cole Johnson, Serge, the MoMA staff, and myself.

Any other points to add? Yes: together with Beanstalk in the private collection was a print of Cinderella, restoring a long-lost final scene (at right) coming after the end of Disney's current element. Looks like Cindy and Prince Charming didn't live happily ever after.

Any other points to add? Yes: together with Beanstalk in the private collection was a print of Cinderella, restoring a long-lost final scene (at right) coming after the end of Disney's current element. Looks like Cindy and Prince Charming didn't live happily ever after.And the latest Whoopee Sketch rundown, as of now:

(Whoopee title • original title)

"Bottle of Rum" = ?

"The Cat's Whiskers" = Puss in Boots

"Egg-Splosion" = non-Disney Bill Nolan short

"The Four Jazz Boys" = Four Musicians of Bremen

"Grandma Steps Out" = Little Red Riding Hood

"The K-O Kid" = Jack the Giant Killer

"On the Up and Up" = Jack and the Beanstalk

"The Peroxide Kid" = Goldie Locks and the Three Bears

"Rural Romeo" = non-Disney Bill Nolan short

"The Slipper-y Kid" = Cinderella

Anyone got that "Bottle of Rum"? LeChuck? Jack Sparrow?... Bootleg Pete?

Special thanks to J. B. Kaufman, Tom Stathes, Timothy Susanin, Michael Barrier, Didier Ghez, Leonard Maltin, Jerry Beck, and Thad Komorowski.

↧

I Taut I Taw New Posts Coming

"You bet you sthaw new posthts coming!"

Er—thanks, Sylvester. As my close friends are well aware, I've been up to my eyeballs in work lately—but that's not to say it hasn't been a lot of fun. I've been editing Fantagraphics' Floyd Gottfredson Library of Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse and writing for Tom Stathes' Bray Animation Project, and I'm looking forward to blogging about both.

But first it's time to welcome you back! As a preview of what's coming, here's a recent find that may not be in its most presentable form, but still answers a few old questions:

The original titles for Tweetie Pie (1947) still don't exist as a whole in any one place—but apart from color, now we know approximately what the viewing experience was like. After I located an unprojectable silent, black and white nitrate neg in a private collection, I fixed up a facsimile by mating still frames from it with the audio located by Larry Tremblay awhile ago (yes, some older TV prints included this track—completely out of sync with the new picture element).

A color element on these original titles has yet to surface. Thad Komorowski has already located other previously unseen color elements from this period, so Tweetie Pie can't be far away.

The credits for Tweetie Pie had been lost for a long time. I'm glad to share them.

The brick wall pictured at the bottom of the Merrie Melodies card was apparently Warners' 1940s method of concealing the "In Technicolor" credit on some black and white prints of color cartoons. I've seen it on a couple of other elements from this period. It fades in and out of view with the Merrie card; it is never (to my knowledge) on other parts of the title sequence.

Here's hoping I don't have to fade out for too long before blogging some more. Thanks for your patience, fellas. (And yours too, Sylvester. Some day you'll eat that darn canary. Weird foods rule.)

Update, August 24: Above, I said: "Thad Komorowski has already located other previously unseen color elements from this era, so Tweetie Pie can't be far away." Sufferin' succotash... the guy moves fast. Thad noticed that Bugs Bunny Superstar (1975) actually showed the title card Tweety image in color, identified there only as a random "Hays Office-approved" character design. Thhanks, Thad:

![]()

Er—thanks, Sylvester. As my close friends are well aware, I've been up to my eyeballs in work lately—but that's not to say it hasn't been a lot of fun. I've been editing Fantagraphics' Floyd Gottfredson Library of Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse and writing for Tom Stathes' Bray Animation Project, and I'm looking forward to blogging about both.

But first it's time to welcome you back! As a preview of what's coming, here's a recent find that may not be in its most presentable form, but still answers a few old questions:

The original titles for Tweetie Pie (1947) still don't exist as a whole in any one place—but apart from color, now we know approximately what the viewing experience was like. After I located an unprojectable silent, black and white nitrate neg in a private collection, I fixed up a facsimile by mating still frames from it with the audio located by Larry Tremblay awhile ago (yes, some older TV prints included this track—completely out of sync with the new picture element).

A color element on these original titles has yet to surface. Thad Komorowski has already located other previously unseen color elements from this period, so Tweetie Pie can't be far away.

The credits for Tweetie Pie had been lost for a long time. I'm glad to share them.

The brick wall pictured at the bottom of the Merrie Melodies card was apparently Warners' 1940s method of concealing the "In Technicolor" credit on some black and white prints of color cartoons. I've seen it on a couple of other elements from this period. It fades in and out of view with the Merrie card; it is never (to my knowledge) on other parts of the title sequence.

Here's hoping I don't have to fade out for too long before blogging some more. Thanks for your patience, fellas. (And yours too, Sylvester. Some day you'll eat that darn canary. Weird foods rule.)

Update, August 24: Above, I said: "Thad Komorowski has already located other previously unseen color elements from this era, so Tweetie Pie can't be far away." Sufferin' succotash... the guy moves fast. Thad noticed that Bugs Bunny Superstar (1975) actually showed the title card Tweety image in color, identified there only as a random "Hays Office-approved" character design. Thhanks, Thad:

↧

↧

2011: One Last Look Back

Happy New Year, everyone. I thought I'd take a (belated) look back at a fond acquaintance whom we lost a couple of months ago.

With his incredible output, writer and researcher Earl Kress made a difference like few others in the animation and comics fields. He’ll be missed; even, unknowingly, by those who wish certain properties were as good as they used to be, and don’t realize that Earl—with his great background knowledge of the properties' history—was the one who made them good.

Beyond this, I'm uncharacteristically at a loss for words; the man's work provides such a perfect testimony.

(Above: From Tom and Jerry Meet Sherlock Holmes [2010], written by Earl Kress. Special thanks to Mike Matei for tech help.)

↧

Notswald: A Ramapith Public Service

How did you try to impress your childhood friends?

My best buddy in third grade was a cartoon fan, like me. We drooled over unaffordable cartoon collectibles that sat, just out of reach, at somber local antique shops. But even if I couldn't afford to own these pricey items, I reasoned, perhaps I could still fool my friend into thinking I owned one.

What was the earliest item of Disney merchandise? A 1929 Mickey Mouse school tablet. Right. What if I'd somehow found an even earlier tablet featuring Oswald the Lucky Rabbit? Of course! This would be easy.

At an art store, I bought the oldest, dingiest yellow construction paper I could find in a back room—so faded and smelly it had to be antique. Then I grabbed a pen and did my best to imitate Ub Iwerks. Wait till my friend saw this! In the words of Disney's later Brer Fox, "it sure gonna fool 'im..."

![]()

Except that in the words of Brer Bear, "it hain't gone fool nobody."

And here the story might have ended.

But for today, when we suddenly find similar fakes moving fast. Multiple Oswald the Lucky Rabbit "poster preliminaries" surfaced on eBay last year, where at least four sold and resold for what became small fortunes. Given my recent history of work with Oswald, several in the animation community have now approached me independently, asking for clarification—are these "preliminaries" authentic 1920s items? Aren't they?

![]()

I won't accuse any specific party of fakery here, because we can't be sure where the items really originated. Some have been rendered on cels, others on rice paper. All have the artwork rendered in elaborate, finished form with black areas (such as Oswald's fur) filled in very dark and solid. Most have extensive black shadowing under the characters. All also have elaborate, scattershot editorial notation added in red pencil. Some notes refer to approvals by Charles Mintz and/or Universal brass. Others indicate changes that were supposedly requested after this stage of the artwork.

![]() It would be interesting to discover that early Disney posters were developed via a multi-step approval system. But all other surviving evidence suggests they weren't. Actual Oswald-era poster sketches were simpler, more lightly-penciled affairs, such as the example for The Fox Chase (1928) at right. The real poster sketches didn't carry copious verbiage: Disney-to-Mintz communication was handled by letters and telegrams at the time. They weren't lavishly finished or inked; at an early stage in which ideas could still be discarded wholesale, there was no need to add excess detail.

It would be interesting to discover that early Disney posters were developed via a multi-step approval system. But all other surviving evidence suggests they weren't. Actual Oswald-era poster sketches were simpler, more lightly-penciled affairs, such as the example for The Fox Chase (1928) at right. The real poster sketches didn't carry copious verbiage: Disney-to-Mintz communication was handled by letters and telegrams at the time. They weren't lavishly finished or inked; at an early stage in which ideas could still be discarded wholesale, there was no need to add excess detail.

Beyond the historical reasons for why this doesn't add up, there are other means by which we can identify fabrications. Finished Oswald posters don't have extensive shadowing like these "preliminaries"; if huge shadows were never to be used in the end, why always include them at an earlier stage? Also, were the "preliminaries" really preliminaries, they would feature pencil construction lines—as seen, again, on Fox Chase—indicating how Oswald was built and the title lettering positioned. On the new "preliminaries," we don't usually see these lines; the art might as well have been traced from the poster reproductions in Russell Merritt and J. B. Kaufman's Walt in Wonderland (1993/2000).

And perhaps it was. Another central point about the newly-surfaced "preliminaries" is that while all 26 Disney Oswald cartoons had posters of their own, the new "preliminaries" all just happen to correspond to the specific handful reproduced in Wonderland. When the reproductions in Wonderland are damaged or incomplete in some way, the "preliminaries" mimic the effects of that damage on the image.

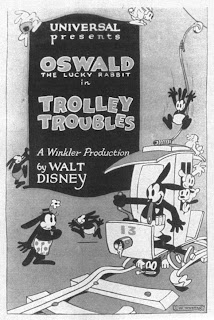

Here is the original one-sheet poster for Trolley Troubles (1927), as reproduced in a black-and-white photo from a major East Coast library collection. This is a rare version of the image, not reprinted anywhere to my knowledge. Gray linework represents elements that were originally outlined in color. Fanny (the girl rabbit) has a big smile. The sideboard containing the title is surrounded by a thin wooden border. The Bunny Kids (Oswald's swarm of children) crouched on top of the sideboard appear in full figure. The trolley bears a large number 13.

![]()

Now here is Trolley Troubles as reproduced in Wonderland, where it comes from Disney's long-held master image: a washed-out, highly faded copy of the earlier photo. This is the version we usually see. The color lines have disappeared, so we lose Fanny's mouth, the edge of the sideboard, the 13 on the trolley and most of the top Bunny Kid figures.

![]()

If a purported "preliminary" for an Oswald poster were genuine, it would include important design elements like mouths. But the newly-surfaced drawings always lack whatever their Wonderland equivalents lack. From Wonderland, for that matter, a forger could also have picked up some historical details for use in his/her red pencil notes.

Be on the lookout for animation art forgeries. They're not worth the high prices that a few of these unlucky rabbits have commanded. And fakery is a lot less endearing when you're a grown person than when you were in third grade.

![]()

Update, June 1: I've removed a photo of one Oswald drawing after receiving a complaint from its present owner. My goal here was merely to discuss the newly-surfaced images—not to embarrass anyone.

My best buddy in third grade was a cartoon fan, like me. We drooled over unaffordable cartoon collectibles that sat, just out of reach, at somber local antique shops. But even if I couldn't afford to own these pricey items, I reasoned, perhaps I could still fool my friend into thinking I owned one.

What was the earliest item of Disney merchandise? A 1929 Mickey Mouse school tablet. Right. What if I'd somehow found an even earlier tablet featuring Oswald the Lucky Rabbit? Of course! This would be easy.

At an art store, I bought the oldest, dingiest yellow construction paper I could find in a back room—so faded and smelly it had to be antique. Then I grabbed a pen and did my best to imitate Ub Iwerks. Wait till my friend saw this! In the words of Disney's later Brer Fox, "it sure gonna fool 'im..."

Except that in the words of Brer Bear, "it hain't gone fool nobody."

And here the story might have ended.

But for today, when we suddenly find similar fakes moving fast. Multiple Oswald the Lucky Rabbit "poster preliminaries" surfaced on eBay last year, where at least four sold and resold for what became small fortunes. Given my recent history of work with Oswald, several in the animation community have now approached me independently, asking for clarification—are these "preliminaries" authentic 1920s items? Aren't they?

I won't accuse any specific party of fakery here, because we can't be sure where the items really originated. Some have been rendered on cels, others on rice paper. All have the artwork rendered in elaborate, finished form with black areas (such as Oswald's fur) filled in very dark and solid. Most have extensive black shadowing under the characters. All also have elaborate, scattershot editorial notation added in red pencil. Some notes refer to approvals by Charles Mintz and/or Universal brass. Others indicate changes that were supposedly requested after this stage of the artwork.

It would be interesting to discover that early Disney posters were developed via a multi-step approval system. But all other surviving evidence suggests they weren't. Actual Oswald-era poster sketches were simpler, more lightly-penciled affairs, such as the example for The Fox Chase (1928) at right. The real poster sketches didn't carry copious verbiage: Disney-to-Mintz communication was handled by letters and telegrams at the time. They weren't lavishly finished or inked; at an early stage in which ideas could still be discarded wholesale, there was no need to add excess detail.

It would be interesting to discover that early Disney posters were developed via a multi-step approval system. But all other surviving evidence suggests they weren't. Actual Oswald-era poster sketches were simpler, more lightly-penciled affairs, such as the example for The Fox Chase (1928) at right. The real poster sketches didn't carry copious verbiage: Disney-to-Mintz communication was handled by letters and telegrams at the time. They weren't lavishly finished or inked; at an early stage in which ideas could still be discarded wholesale, there was no need to add excess detail.Beyond the historical reasons for why this doesn't add up, there are other means by which we can identify fabrications. Finished Oswald posters don't have extensive shadowing like these "preliminaries"; if huge shadows were never to be used in the end, why always include them at an earlier stage? Also, were the "preliminaries" really preliminaries, they would feature pencil construction lines—as seen, again, on Fox Chase—indicating how Oswald was built and the title lettering positioned. On the new "preliminaries," we don't usually see these lines; the art might as well have been traced from the poster reproductions in Russell Merritt and J. B. Kaufman's Walt in Wonderland (1993/2000).

And perhaps it was. Another central point about the newly-surfaced "preliminaries" is that while all 26 Disney Oswald cartoons had posters of their own, the new "preliminaries" all just happen to correspond to the specific handful reproduced in Wonderland. When the reproductions in Wonderland are damaged or incomplete in some way, the "preliminaries" mimic the effects of that damage on the image.

Here is the original one-sheet poster for Trolley Troubles (1927), as reproduced in a black-and-white photo from a major East Coast library collection. This is a rare version of the image, not reprinted anywhere to my knowledge. Gray linework represents elements that were originally outlined in color. Fanny (the girl rabbit) has a big smile. The sideboard containing the title is surrounded by a thin wooden border. The Bunny Kids (Oswald's swarm of children) crouched on top of the sideboard appear in full figure. The trolley bears a large number 13.

Now here is Trolley Troubles as reproduced in Wonderland, where it comes from Disney's long-held master image: a washed-out, highly faded copy of the earlier photo. This is the version we usually see. The color lines have disappeared, so we lose Fanny's mouth, the edge of the sideboard, the 13 on the trolley and most of the top Bunny Kid figures.

If a purported "preliminary" for an Oswald poster were genuine, it would include important design elements like mouths. But the newly-surfaced drawings always lack whatever their Wonderland equivalents lack. From Wonderland, for that matter, a forger could also have picked up some historical details for use in his/her red pencil notes.

Be on the lookout for animation art forgeries. They're not worth the high prices that a few of these unlucky rabbits have commanded. And fakery is a lot less endearing when you're a grown person than when you were in third grade.

Update, June 1: I've removed a photo of one Oswald drawing after receiving a complaint from its present owner. My goal here was merely to discuss the newly-surfaced images—not to embarrass anyone.

↧

Cele-bray-ting Historic Silents

If my friends were asked to name my favorite cartoon stars, various high-pitched, black-furred animals might come to mind. But I'm also fascinated by a group of earlier, cruder, yet still endearing animated creations. Judge Rummy, Bobby Bumps, and Jerry on the Job were among the leading lights at Bray Studios, the first fullscale cartoon production house in the United States.

They are also almost completely forgotten today.

T'was not always thus, of course. Bray would never have gone fullscale had his films not been successful. J. R. Bray (1879-1978) cut his pop culture teeth in the early 1900s, with a variety of comic strips based on dachshunds. (We've all got to start somewhere.) From this he moved onward to his first successful Sunday newspaper series—Little Johnny and the Teddy Bears—and in 1913, his first animated shorts. Film number four, Colonel Heeza Liar in Africa (1913), introduced the first recurring American cartoon star, a windy little explorer who would feature on and off in Bray cartoons for some twelve years.

Bolstered by Heeza's growing success, Bray Studios expanded; cut distribution deals with the likes of Paramount and Goldwyn Pictures, and hired a raft of additional cartoonists and auteurs, all of whom were soon directing films of their own. Earl Hurd created Bobby Bumps and his dour dog Fido. Paul Terry flung Farmer Al Falfa into action. Max Fleischer created Koko the Clown, called only "the Goldwyn-Bray Clown" at the time.

But Bray's star-packed stable lost mileage fast. The demanding producer rarely saw eye-to-eye with his staffers; eventually, he found many of them departing to start their own studios, taking their characters with them. In time, Bray Studios moved into educational media. After a brief revival on 1950s TV, Bray's cartoon heyday became a footnote in history.

Of course, for me Bray is alive and well. For the past year, I've been heavily active with my friend Tom Stathes, founder of the Bray Animation Project website; and the business of rediscovering—and locating—their long-lost films has become a surprising, exciting adventure for us. Before now, it seemed few scholars noticed Bray. Today we are traveling from archive to archive: researching scrapbooks and production materials, making note of the studio's groundbreaking technical innovations and wry, often adult-themed content.

Of course, for me Bray is alive and well. For the past year, I've been heavily active with my friend Tom Stathes, founder of the Bray Animation Project website; and the business of rediscovering—and locating—their long-lost films has become a surprising, exciting adventure for us. Before now, it seemed few scholars noticed Bray. Today we are traveling from archive to archive: researching scrapbooks and production materials, making note of the studio's groundbreaking technical innovations and wry, often adult-themed content.In the process of all this research, Tom and I have also sought out 16mm prints of the Bray subjects. Already known for his extensive silent cartoon library, Tom has a special focus on Bray, and I'm pleased to have helped him with his acquisitions. Now we're planning some exciting DVDs... but I say too much!

For the moment, the excitement is about the Bray Project's first anniversary. In just one year's time, the initiative has made exciting progress. Collectors with scarce prints have contacted us; even rare animation art has turned up—and with it some pleasant surprises.

Bray partner Earl Hurd patented the process of cel animation in late 1914. Cels allowed characters to be painted on transparent celluloid and laid over complex backgrounds; earlier, most cartoons consisted of line art, with simple backgrounds meticulously traced from picture to picture.

|

| Colonel Heeza Liar, Dog Fancier (1915) |

This method sounds easy in practice, but was cumbersome in execution; to a point in which it is often described as having been discarded after Bray's first several films. What a surprise, then, to find that Bray actually continued to use it, in various permutations, well into 1915 and for quite a number of shorts.

With Colonel Heeza Liar in Mexico (1914), the comparison of an unused background sheet with a finished frame show how Heeza and the stork were drawn and painted image by image. This wasn't so different from the later cel process. But with Bray's method, some nonmoving rooftops had to be repainted on every drawing, too.

For Rastus' Rabid Rabbit Hunt (1914), the printed background seems minimal: just a horizon line and a cow. But a close look at the back of the sheet—where ink lines vary in strength—reveals that Rastus (the sadly stereotyped African-American hunter) held still for this part of the shot, so he was printed as part of the background too. Poor Rastus had to be painted anew in every frame, even when totally motionless.

The cel system couldn't come soon enough.

|

| Bray-era publicity drawing, 1916 |

I'd also like to bring you one more Bray rarity right here, right now.

In 1920, following a deal with Hearst's International Film Service, the Bray studio began to produce Krazy Kat shorts; the second series of films with George Herriman's perennial patsy. Some are lost today; and some, like The Best Mouse Loses (1920), are most often seen in truncated, virtually plotless excerpts. The edited Best Mouse feels like a rudimentary exercise in animation: mice dance around a boxing ring, with no obvious rhyme or reason to their actions.

Now, with thanks to Tom and the Bray Animation Project, I'm pleased to share the complete The Best Mouse Loses—which actually features a sophisticated storyline. Ignatz Mouse has a cunning plan, his wife Magnolia has another... and poor Krazy Kat learns that it always hurts to help.

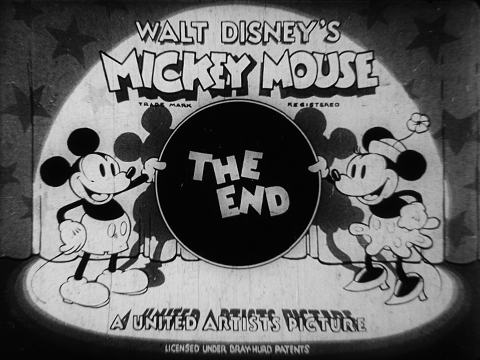

Some of you may remember the Bray name from some more famous mouse films. Thanks to his patents on the animation process, here's where he cropped up in 1932...

(Hey, is that an original end title? Yes—there's another big blogpost in the works, whenever I get time. Fingers crossed.)

As a final note, I'd like to ask that if you use any of this blogpost's Bray images elsewhere, you please credit Tom Stathes, myself, and the Bray Project. As the old proverb sort of goes:

Bray screen in the morning, Heeza's warning.

Bray screen at night, Heeza's delight!

↧

Mouse, Interrupted

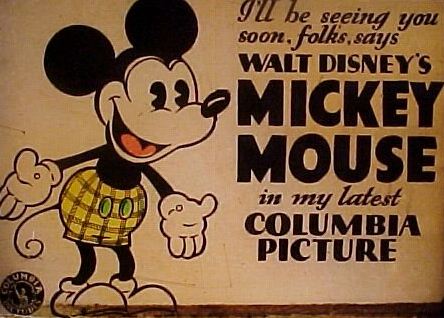

Once upon a time—way back in the 1930s—Columbia Pictures and United Artists released Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse cartoons to theatres. But Columbia and United Artists had nothing to do with the cartoons' non-theatrical distribution. So a few years later, when Disney prepared reissue versions for home and TV use, the original Columbia and United Artists main and end title sequences were replaced.

This led to the birth of the "burlap titles" shown here: so-called due to their cloth-like background texture. The burlap titles were printed on safety film stock and spliced into Disney's nitrate negatives. While appealing, they did have a certain sameness. All used the same logotype for Mickey's name, the same font for each cartoon's episode title, and the same musical notes tossing and turning behind.

The more unique original title sequences seemed to have vanished for parts unknown. Only occasional early release prints were known to preserve them; and in the 1990s, when the vintage Mickey cartoons were restored for laser, VHS, and DVD, only a few such early prints could be found at Disney.

Animation fans know what happened next. In an effort to return to the original style for home video, "faux" original titles were created to replace their burlap precursors. But while the results were a beautiful improvement, they couldn't quell my curiosity. As a contributing scholar when they were created, I still wanted to see the real originals.

Over the eight (in some cases, nineteen) years since the faux titles' creation, I've searched through private collections and film dealers' backstock in an effort to locate as many originals as I could. I even bought a few, despite my not usually collecting sound films. Over time, I've come across roughly two dozen title sequences, several of which I've shared here in the past. I've saved most, though, for this post: where, looking at them in sequence, we can gain a better understanding of how the title designs evolved.

We may even get a few surprises!

The Cactus Kid (1930) shows us how we'll look at most of these titles: with the originals on the left, and the recreations on the right—

The first Columbia main title design featured thick white lettering on a dark gray background. Whereas earlier and later Mickey opening titles concluded with most of the card fading out, so only the episode title was seen (as in the recreation)—on the first Columbia shorts, the whole card faded out as one unit, title and all.

The first Columbia end title design cloned the 1928-29 Celebrity Pictures look, with goggle-eyed proto-Mickey and Minnie. Only the text under the figures has changed to indicate Columbia.

The recreated titles for Cactus Kid used later Columbia title cards as design templates. At the time, researchers (myself included) didn't know that the earlier Columbia cards looked any different; thus the understandable discrepancy.

A later Mickey headshot was also added to the start of the recreated Columbia titles; originally, the Columbia Mickey shorts had no headshot.

By the time of The Shindig (1930) things began to change. The better-known Columbia end title was now used, though I don't yet know whether The Shindig was the first cartoon to use it:

Pioneer Days (1930) is the earliest title where Disney itself has publicly released a newly-located original element. It didn't make the American DVD release in 2003, but for the disc's later issue in Europe, it was swapped in.

You'll notice that this time the episode title remains on-screen when most of the title card fades out. I don't know if Pioneer Days was the first Columbia Mickey to use this technique, but it's the earliest example I've thus far seen:

The Castaway (1931) was shown with original titles on the Disney Channel in the 1980s, but cropped tight so the Columbia references weren't visible. Here is the whole image (and its 1990s recreation, very close this time):

Unlike many of the elements I've accessed and studied, the original Delivery Boy (1931) was able to be viewed. Here are its main titles courtesy of my friend and colleague Tom Stathes (compare with the very close recreated version here):

Well into 1932, Columbia's Mickey title cards were still using primitive 1930 Mickey and Minnie character models. Interesting how they hadn't been supplanted with streamlined designs. Maybe a little too interesting... for gosh sakes, what's this?

In spring 1932, when United Artists was preparing to replace Columbia as Mickey distributor, this promo image appeared in a Kay Kamen trade catalog. Drawn unmistakably by Floyd Gottfredson's comics team, it appears to be an intended update of the Columbia title card design.

Nevertheless, I have seen no film elements that include it—Columbia or otherwise. Columbia kept their 1930 design to the bitter end, and then the first United Artists titles looked like this:

The recreated version this time comes from among the first recreations done. At that time, it was evidently preferred not to mention United Artists, thus the omission of their name.

The recreated title sequences for this and other United Artists cartoons tend to feature the episode title zooming toward us as the rest of the card fades away. Original United Artists Mickeys were famous for this technique—but as I've only recently learned, they didn't introduce it until 1933.

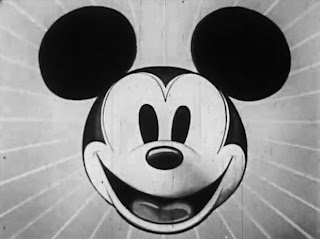

Mickey's Nightmare (1932) was the first Mickey cartoon to open with a Mickey headshot on its initial release. The subsequent Trader Mickey (1932) had it too:

The recreated versions here are based on 1974 reissue titles for seven United Artists-era black and white shorts (not including Trader Mickey). The 1974 end title matches the 1974 main title for design and character poses. Both are staged from further away than the original 1932 image—so that 1970s theatres could crop them on the top and bottom for widescreen.

The opening headshot stayed as-is. At this point, we see that it isn't meant to be Mickey's "real" head—but rather a kind of sparkler toy. The beams of light whirl around it wildly and seem to come from within, as well as from behind. And then Mickey's face... well... er, see for yourself!

Somewhere, "Exploding Mickey" sits on a therapist's couch alongside the Lumber-Jack Rabbit Warner Bros shield, asking their mutual shrink how they can apologize to the many kids they've scared.