Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

If my friends were asked to name my favorite cartoon stars, various high-pitched, black-furred animals might come to mind. But I'm also fascinated by a group of earlier, cruder, yet still endearing animated creations. Judge Rummy, Bobby Bumps, and Jerry on the Job were among the leading lights at Bray Studios, the first fullscale cartoon production house in the United States.

They are also almost completely forgotten today.

T'was not always thus, of course. Bray would never have gone fullscale had his films not been successful. J. R. Bray (1879-1978) cut his pop culture teeth in the early 1900s, with a variety of comic strips based on dachshunds. (We've all got to start somewhere.) From this he moved onward to his first successful Sunday newspaper series—Little Johnny and the Teddy Bears—and in 1913, his first animated shorts. Film number four, Colonel Heeza Liar in Africa (1913), introduced the first recurring American cartoon star, a windy little explorer who would feature on and off in Bray cartoons for some twelve years.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Bolstered by Heeza's growing success, Bray Studios expanded; cut distribution deals with the likes of Paramount and Goldwyn Pictures, and hired a raft of additional cartoonists and auteurs, all of whom were soon directing films of their own. Earl Hurd created Bobby Bumps and his dour dog Fido. Paul Terry flung Farmer Al Falfa into action. Max Fleischer created Koko the Clown, called only "the Goldwyn-Bray Clown" at the time.

But Bray's star-packed stable lost mileage fast. The demanding producer rarely saw eye-to-eye with his staffers; eventually, he found many of them departing to start their own studios, taking their characters with them. In time, Bray Studios moved into educational media. After a brief revival on 1950s TV, Bray's cartoon heyday became a footnote in history.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Of course, for me Bray is alive and well. For the past year, I've been heavily active with my friend Tom Stathes, founder of the Bray Animation Project website; and the business of rediscovering—and locating—their long-lost films has become a surprising, exciting adventure for us. Before now, it seemed few scholars noticed Bray. Today we are traveling from archive to archive: researching scrapbooks and production materials, making note of the studio's groundbreaking technical innovations and wry, often adult-themed content.

Of course, for me Bray is alive and well. For the past year, I've been heavily active with my friend Tom Stathes, founder of the Bray Animation Project website; and the business of rediscovering—and locating—their long-lost films has become a surprising, exciting adventure for us. Before now, it seemed few scholars noticed Bray. Today we are traveling from archive to archive: researching scrapbooks and production materials, making note of the studio's groundbreaking technical innovations and wry, often adult-themed content.

In the process of all this research, Tom and I have also sought out 16mm prints of the Bray subjects. Already known for his extensive silent cartoon library, Tom has a special focus on Bray, and I'm pleased to have helped him with his acquisitions. Now we're planning some exciting DVDs... but I say too much!

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

For the moment, the excitement is about the Bray Project's first anniversary. In just one year's time, the initiative has made exciting progress. Collectors with scarce prints have contacted us; even rare animation art has turned up—and with it some pleasant surprises.

Bray partner Earl Hurd patented the process of cel animation in late 1914. Cels allowed characters to be painted on transparent celluloid and laid over complex backgrounds; earlier, most cartoons consisted of line art, with simple backgrounds meticulously traced from picture to picture.

What many forget is that there was an intermediate step. Prior to Hurd's cel system, Bray attempted to patent a borderline process in which partial backgrounds—with gaps for the action to take place—were mechanically reprinted on translucent paper. Then animators filled in the gap on every sheet, "animat[ing] only the part of the scene that had to move" (Maltin, 1978). The sheets' translucent nature enabled them to be painted on the back, creating shading.

This method sounds easy in practice, but was cumbersome in execution; to a point in which it is often described as having been discarded after Bray's first several films. What a surprise, then, to find that Bray actually continued to use it, in various permutations, well into 1915 and for quite a number of shorts.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

With Colonel Heeza Liar in Mexico (1914), the comparison of an unused background sheet with a finished frame show how Heeza and the stork were drawn and painted image by image. This wasn't so different from the later cel process. But with Bray's method, some nonmoving rooftops had to be repainted on every drawing, too.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

For Rastus' Rabid Rabbit Hunt (1914), the printed background seems minimal: just a horizon line and a cow. But a close look at the back of the sheet—where ink lines vary in strength—reveals that Rastus (the sadly stereotyped African-American hunter) held still for this part of the shot, so he was printed as part of the background too. Poor Rastus had to be painted anew in every frame, even when totally motionless.

The cel system couldn't come soon enough.

There are more Bray discoveries looming up ahead—many more. For the moment, allow me to suggest that you come to Tom's next Cartoon Carnival screening, Friday, June 8—in which we'll feature a very rare Bray Katzenjammer Kids cartoon.

I'd also like to bring you one more Bray rarity right here, right now.

In 1920, following a deal with Hearst's International Film Service, the Bray studio began to produce Krazy Kat shorts; the second series of films with George Herriman's perennial patsy. Some are lost today; and some, like The Best Mouse Loses (1920), are most often seen in truncated, virtually plotless excerpts. The edited Best Mouse feels like a rudimentary exercise in animation: mice dance around a boxing ring, with no obvious rhyme or reason to their actions.

Now, with thanks to Tom and the Bray Animation Project, I'm pleased to share the complete The Best Mouse Loses—which actually features a sophisticated storyline. Ignatz Mouse has a cunning plan, his wife Magnolia has another... and poor Krazy Kat learns that it always hurts to help.

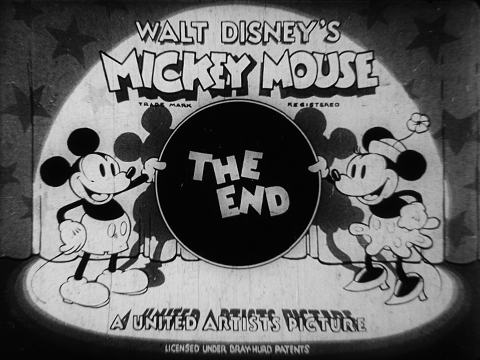

Some of you may remember the Bray name from some more famous mouse films. Thanks to his patents on the animation process, here's where he cropped up in 1932...

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

(Hey, is that an original end title? Yes—there's another big blogpost in the works, whenever I get time. Fingers crossed.)

As a final note, I'd like to ask that if you use any of this blogpost's Bray images elsewhere, you please credit Tom Stathes, myself, and the Bray Project. As the old proverb sort of goes:

Bray screen in the morning, Heeza's warning.

Bray screen at night, Heeza's delight!

Clik here to view.

If my friends were asked to name my favorite cartoon stars, various high-pitched, black-furred animals might come to mind. But I'm also fascinated by a group of earlier, cruder, yet still endearing animated creations. Judge Rummy, Bobby Bumps, and Jerry on the Job were among the leading lights at Bray Studios, the first fullscale cartoon production house in the United States.

They are also almost completely forgotten today.

T'was not always thus, of course. Bray would never have gone fullscale had his films not been successful. J. R. Bray (1879-1978) cut his pop culture teeth in the early 1900s, with a variety of comic strips based on dachshunds. (We've all got to start somewhere.) From this he moved onward to his first successful Sunday newspaper series—Little Johnny and the Teddy Bears—and in 1913, his first animated shorts. Film number four, Colonel Heeza Liar in Africa (1913), introduced the first recurring American cartoon star, a windy little explorer who would feature on and off in Bray cartoons for some twelve years.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Bolstered by Heeza's growing success, Bray Studios expanded; cut distribution deals with the likes of Paramount and Goldwyn Pictures, and hired a raft of additional cartoonists and auteurs, all of whom were soon directing films of their own. Earl Hurd created Bobby Bumps and his dour dog Fido. Paul Terry flung Farmer Al Falfa into action. Max Fleischer created Koko the Clown, called only "the Goldwyn-Bray Clown" at the time.

But Bray's star-packed stable lost mileage fast. The demanding producer rarely saw eye-to-eye with his staffers; eventually, he found many of them departing to start their own studios, taking their characters with them. In time, Bray Studios moved into educational media. After a brief revival on 1950s TV, Bray's cartoon heyday became a footnote in history.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Of course, for me Bray is alive and well. For the past year, I've been heavily active with my friend Tom Stathes, founder of the Bray Animation Project website; and the business of rediscovering—and locating—their long-lost films has become a surprising, exciting adventure for us. Before now, it seemed few scholars noticed Bray. Today we are traveling from archive to archive: researching scrapbooks and production materials, making note of the studio's groundbreaking technical innovations and wry, often adult-themed content.

Of course, for me Bray is alive and well. For the past year, I've been heavily active with my friend Tom Stathes, founder of the Bray Animation Project website; and the business of rediscovering—and locating—their long-lost films has become a surprising, exciting adventure for us. Before now, it seemed few scholars noticed Bray. Today we are traveling from archive to archive: researching scrapbooks and production materials, making note of the studio's groundbreaking technical innovations and wry, often adult-themed content.In the process of all this research, Tom and I have also sought out 16mm prints of the Bray subjects. Already known for his extensive silent cartoon library, Tom has a special focus on Bray, and I'm pleased to have helped him with his acquisitions. Now we're planning some exciting DVDs... but I say too much!

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

For the moment, the excitement is about the Bray Project's first anniversary. In just one year's time, the initiative has made exciting progress. Collectors with scarce prints have contacted us; even rare animation art has turned up—and with it some pleasant surprises.

Bray partner Earl Hurd patented the process of cel animation in late 1914. Cels allowed characters to be painted on transparent celluloid and laid over complex backgrounds; earlier, most cartoons consisted of line art, with simple backgrounds meticulously traced from picture to picture.

| Image may be NSFW. Clik here to view.  |

| Colonel Heeza Liar, Dog Fancier (1915) |

This method sounds easy in practice, but was cumbersome in execution; to a point in which it is often described as having been discarded after Bray's first several films. What a surprise, then, to find that Bray actually continued to use it, in various permutations, well into 1915 and for quite a number of shorts.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

With Colonel Heeza Liar in Mexico (1914), the comparison of an unused background sheet with a finished frame show how Heeza and the stork were drawn and painted image by image. This wasn't so different from the later cel process. But with Bray's method, some nonmoving rooftops had to be repainted on every drawing, too.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

For Rastus' Rabid Rabbit Hunt (1914), the printed background seems minimal: just a horizon line and a cow. But a close look at the back of the sheet—where ink lines vary in strength—reveals that Rastus (the sadly stereotyped African-American hunter) held still for this part of the shot, so he was printed as part of the background too. Poor Rastus had to be painted anew in every frame, even when totally motionless.

The cel system couldn't come soon enough.

| Image may be NSFW. Clik here to view.  |

| Bray-era publicity drawing, 1916 |

I'd also like to bring you one more Bray rarity right here, right now.

In 1920, following a deal with Hearst's International Film Service, the Bray studio began to produce Krazy Kat shorts; the second series of films with George Herriman's perennial patsy. Some are lost today; and some, like The Best Mouse Loses (1920), are most often seen in truncated, virtually plotless excerpts. The edited Best Mouse feels like a rudimentary exercise in animation: mice dance around a boxing ring, with no obvious rhyme or reason to their actions.

Now, with thanks to Tom and the Bray Animation Project, I'm pleased to share the complete The Best Mouse Loses—which actually features a sophisticated storyline. Ignatz Mouse has a cunning plan, his wife Magnolia has another... and poor Krazy Kat learns that it always hurts to help.

Some of you may remember the Bray name from some more famous mouse films. Thanks to his patents on the animation process, here's where he cropped up in 1932...

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

(Hey, is that an original end title? Yes—there's another big blogpost in the works, whenever I get time. Fingers crossed.)

As a final note, I'd like to ask that if you use any of this blogpost's Bray images elsewhere, you please credit Tom Stathes, myself, and the Bray Project. As the old proverb sort of goes:

Bray screen in the morning, Heeza's warning.

Bray screen at night, Heeza's delight!