Wayne Allwine will be missed.

Wayne Allwine will be missed.I'm not the first to say so. In fact, my blog must be about the five-hundredth cartoon blog to spread the news, insofar as Disney's longtime Mickey Mouse voice artist actually passed away several weeks ago. But I'm going to regret Allwine's loss not just for what he did, but what he could—fate permitting—have done so much more of, because he was so incredibly right for it.

Allwine's Mickey Mouse was featured most often in the context of light entertainment—most often aimed specifically at kids. From his first work in the New Mickey Mouse Club (1977) through numerous sing-along records and the Mickey Mouse Clubhouse TV series (2006-present), Allwine typically portrayed a mouse who was primarily a substitute parent for toddlers; a bubbly, gently authoritative man-child, but little more. This Mickey was rarely depressed or conflicted, nor did he have reason to be. On the other hand, I can't blame Allwine for having delivered the kind of host character that preschool entertainment often demands. He was asked to do it, and he was fine at that.

It's just that Mickey can be more than that character. Disney comics fans know that in the pages of four-color funnies, Mickey is a star aimed at all ages; not just children. Instead of an adult, establishment role model, the best comics portray "a mouse against the world": a stubbornly optimistic, imperfect but determined youth trying to prove himself in competitive and downright dangerous situations and surroundings. And in funny business—because an earnest, struggling underdog can get into awfully embarrassing scrapes, too.

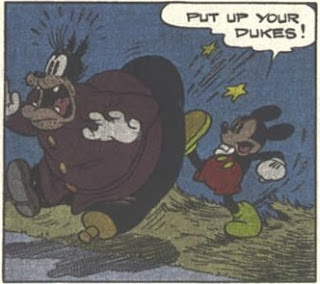

It's just that Mickey can be more than that character. Disney comics fans know that in the pages of four-color funnies, Mickey is a star aimed at all ages; not just children. Instead of an adult, establishment role model, the best comics portray "a mouse against the world": a stubbornly optimistic, imperfect but determined youth trying to prove himself in competitive and downright dangerous situations and surroundings. And in funny business—because an earnest, struggling underdog can get into awfully embarrassing scrapes, too.This is the Mickey developed first by Floyd Gottfredson in the 1930s dailies; the Mickey who battled Pegleg Pete on fighter planes and escaped from the Phantom Blot's deathtraps. And tried to get out of modeling dresses for Minnie, "doggone th' luck!"

In Runaway Brain (1995) and the Mouseworks and House of Mouse series (1999-2003), as well as its Three Musketeers companion film (2004), Allwine finally got precious chances to portray something close to this version of Mickey. While every project had its arguable drawbacks—these obviously weren't golden age cartoons—we did get to see Mickey the smart aleck again; Mickey the underdog; even Mickey the dramatist, perhaps more than in any animated incarnation. And Allwine delivered the voicework in a way that, I think, Jimmy MacDonald never could.

Let me show you what I'm talking about with a little "best-of" compilation that I've put together. You'll have to put up with sometimes-crude TV animation to enjoy the Allwine acting, but maybe if I throw the Phantom Blot into the mix...

Ironically, Mickey Foils the Phantom Blot (1999) was also the exception that proved the rule. As enjoyable as aspects of Mouseworks and Three Musketeers were, the best opportunity never materialized: there was never, during Allwine's lifetime, a real series of long-form Mickey adventure cartoons made, nor was a chance taken to actually adapt any comics characters or environments beyond the Blot and—briefly—the relatively unimportant Chief O'Hara. We can only imagine, most of the time, how well Allwine's Mickey would fit into the full environment of the comics character.

Luckily, we don't have to imagine all the time, thanks to a few rather uncommon Allwine performances I'm pleased to share. In the mid-1990s, Disney mounted a promotional campaign called "The Perils of Mickey," consisting of merchandise based on several classic Gottfredson comics adventures. Was a plan ever made to expand this push into animation? I don't know, but I'm certain that at some point, it expanded into recordings. An abbreviated version of Gottfredson's classic "Blaggard Castle" (1932), pitting Mickey and Horace Horsecollar against Professors Ecks, Doublex, and Triplex, was recorded as a Disney "storyteller album" with Allwine and others in the roles. It doesn't seem ever to have been released that way, but one can find it on ITunes and Amazon now—minus the "Perils" branding. In the spirit of fair use (sorry, you'll have to buy the whole thing if you want it!), here's a little excerpt, complete with the corresponding Gottfredson strips for comparison:

Luckily, we don't have to imagine all the time, thanks to a few rather uncommon Allwine performances I'm pleased to share. In the mid-1990s, Disney mounted a promotional campaign called "The Perils of Mickey," consisting of merchandise based on several classic Gottfredson comics adventures. Was a plan ever made to expand this push into animation? I don't know, but I'm certain that at some point, it expanded into recordings. An abbreviated version of Gottfredson's classic "Blaggard Castle" (1932), pitting Mickey and Horace Horsecollar against Professors Ecks, Doublex, and Triplex, was recorded as a Disney "storyteller album" with Allwine and others in the roles. It doesn't seem ever to have been released that way, but one can find it on ITunes and Amazon now—minus the "Perils" branding. In the spirit of fair use (sorry, you'll have to buy the whole thing if you want it!), here's a little excerpt, complete with the corresponding Gottfredson strips for comparison:

"Blaggard Castle" wasn't the only time Allwine would record Gottfredson, either. In 1938, Western Publishing issued a series of Disney storybooks with blandly generic titles—The Story of Mickey Mouse, The Story of Dippy the Goof, and so forth—containing Big Little Book-like retellings of Gottfredson Sunday gag pages. In 1996, Applewood Press reprinted these books with accompanying CDs, each containing recorded versions of the books' texts with then-current Disney voice actors in the roles. Here's Ted Osborne's and Floyd Gottfredson's Mickey Mouse Sunday page for November 29, 1936...

...and here's Allwine's reenactment. To make it more like the Sunday page and less like the book, I've eliminated the narration that originally bridged the dialogue...

(Oh, okay. You want to hear the narration, too? Here's the complete version, with Horace's voice actor narrating as Horace. I'm not sure it's the more recent Bill Farmer here, but I could be wrong...)

Let's hear it for Wayne Allwine—a man who didn't live in the golden age of animation, but who was capable of a wonderful golden age Mickey Mouse. (And if any of my readers knows more of the backstory behind the "Blaggard Castle" recording, I'd be grateful for a scoop.)